America is going to talk about Beef for a long time. The show is hitting larger zeitgeist. You don’t have to be Asian to get many aspects of Beef. America is a very angry country at the moment. The revenge in Beef is fueled by social media and the internet. I know that people my children’s age (Gen Z) can’t imagine a time without social media or the internet and on demand streaming. My children couldn’t stop laughing when I told them when I was in junior high school we would talk about getting home in time to watch the latest Michael Jackson video on MTV. What no live streaming? You didn’t even have cell phones back then. How did you know what time it was was? We have watches, or specifically Swatches.

We are living in an era of vitriolic social media feuds where people can access each other’s personal information and whereabouts in ways that were not possible before the internet. We are living in an era where unhappy people with too much free time can target anyone else online for the most trivial reason. We are living in an era where anyone feels power by leaving a negative review. We are living in an era where this power, however false, can be exercised anonymously.

Years ago, an Indian American professor felt slighted because I disagreed with his Korean American wife’s Korean restaurant reccomendation. This professor preceded to troll me and my husband online for over five years. He wrote bad reviews about our recipes that were published in Gourmet Magazine, “tastes like MacDonalds”. He trolled us on food forums for grammatical errors. Yes, the Indian professor was an English professor. It was the beginning of on demand revenge in America. Without the internet and the ability to comment on any published article, this professor and I would have never crossed paths again.

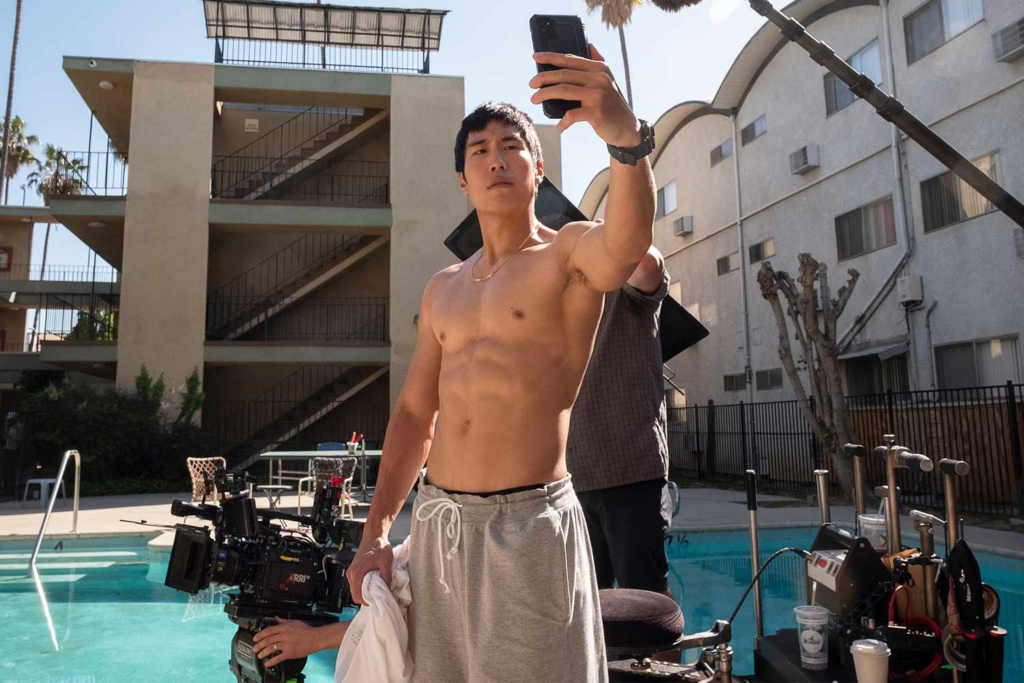

Asian America is going to talk about Beef for a long time. It’s going to ride into this fall and beyond. Everyday there are new takes on another aspect of Beef, whether it’s how Asian American men are represented or how beef nailed the Korean family dynamics or the Korean church.

The cartography of Beef is my home town. I know all the Asian American characters in Beef. I’ve been in their spaces and inside their homes. I’ve eaten with them. Beef is a game changer for Asian American creatives behind the scenes and in front of the scenes.

I have never felt this seen and this satisfied with Asian American representation.

I live a few blocks away from Hanbat Shul Lung Tang, the Korean soup restaurant where Danny’s family goes to eat. I location sourced the restaurant for Andrew Zimmern’s show. Yes, I met Andrew. No comment. Hanbat opened in 1988. It’s one of those restaurants that practically every Korean in LA City knows about.

I chortled when Danny ended up at Arena night club. I don’t go to night clubs, but even I know about this place. It’s a hard pumping party place. Late at night, I’ve seen Korean men and women so drunk that they have to carried by their friends, sometimes while sobbing.

My cousin is the lead pastor at a second generation Korean American church. My kids used to go to his church and my mother’s church. My kids went to Saturday Korean school at OMC (Oriental Mission Church) for several years.

The juxtaposition of Amy and George in a sterile Western pyschological space with Amy cynically repeating what she thinks George and the Asian American pyschologist want to hear; and Danny sobbing at a Korean American church is nothing short of brilliant. Neither setting is satisfying or healing. Neither method really works. I’ve watched the clip of Danny singing Amazing Grace over a dozen times. How is Steven Yeun this multi-talented? And I’ve been in that space feeling the same emotions.

My 19 year old son saw Steven Yeun at Salt and Straw on Larchmont Blvd. My 24 year old daughter and I saw Conan O’Brian crossing the street towards us on Larchmont Blvd. Larchmont is adjacent to Koreatown. I remember when I was 26 years old, a white woman said to me that Larchmont Village isn’t a place for “your kind.” In 1994, The Los Angeles Times published a racially loaded article about the Koreans moving into Hancock Park. Now Larchmont Village is brimming with Koreans and the staff at Salt and Straw are giddy that Steven Yeun and a member of BTS patronized them.

My deceased aunt lived in Westlake Village for four decades. In a gated community, no less. I went to junior high school in Tarzana. Calabassas is smack in between Westlake Village and Tarzana. I know the rich West Valley Koreans too. Naomi is someone I know. A Korean American friend of mine lives in nearby Encino and she does things like jetting around America with her friends to eat at the priciest restaurants from New York to Sonoma. Her uncle owns a private jet company. She invited me over to her house when she flew in Buddhist monk chef Jeong Kwan of Netflix Chef’s Table fame. The famous chef cooked for us. This is the most exclusive dining experience. You can’t buy it with money. You need to know someone who can fly in a famous Buddhist monk chef and thinks you’re just right for the experience.

I’m friends with or aquaintances with numerous people involved with Gyopo US. They helped me fundraise for homeless Koreans and I was a panelist on one of their programs. I found at that Joseph Lee (George) did an exhibtion with Gyopo US and a Korean American clothing designer that my daughter models for once dated Joseph. I’m familiar with Amy, George, and Fumi and their cartography. Gyopo US does a lot of cool, grassroots programming. But they’re affiliated with elite or luxury Korean diasporic artists who curate or exhibit at world class museums all over the world.

I’ve read numerous takes on Beef written by Asian Americans who grew up in the 1990s or 1980s. I grew up in the 1970s and 1980s. I’ve lived in Los Angeles for over 48 years and I really needed to see Asian American rage and complexities portrayed on screen.

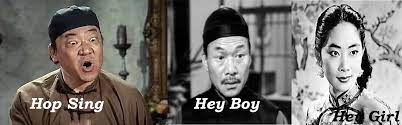

The 1970s were a dismal decade for Asian American representation on screen. I remember watching reruns of The Courtship of Eddie’s Father with my brothers. We just wanted to see an Asian face on screen. I don’t even remember the particulars of the show. I only remember Miyoshi Umeki playing a maid and saying, “Mr. Eddie’s father” with a heavy Japanese accent. Eddie was an elementary school aged child that an Asian maid called “Mr.” I choked on that one. A few kids at school asked me if the maid was my mom.

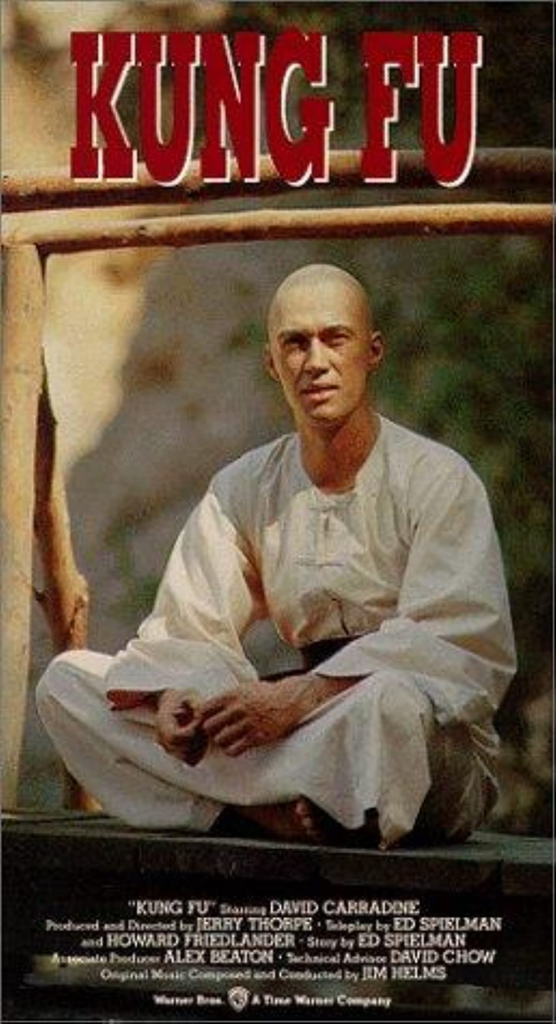

My brothers and I also watched Kung Fu starring David Carradine as a Chinese man. Yes, a few kids at school thought it was funny to constantly tell me to snatch a pebble from their hand. At a time when there was so little Asian representation on screen, kids at school associated ANY representation with me or my brothers.

Asians were incidental and minor characters in any number of American westerns. But the portrayals were always deliberately racist, demeaning, or caricatures. In other words propagandistic “weird, perpetual foreigners”. Off the top of my head, I don’t remember them being more than cooks, laundry workers, domestic servants, or dragon ladies.

My brothers and I really enjoyed watching Hong Kong martial arts films. But this was a double edged sword. We were also constantly asked if Bruce Lee is our uncle and to show off some kung fu skills by other kids at school.

One day, when I was in elementary school and my brothers were in Junior high and high school, we were walking in the San Fernando Valley with Kenny, a Cantonese American friend. His family was from Hong Kong. A group of kids started teasing us and calling us racial slurs. They eventually asked us if we knew Kung Fu. We said, “Yes” and started fighting back and beat them up. My brothers and I had were taking Tae Kwon Do and Kenny was taking Kung Fu at the time. So yeah, Asians do get angry and we fight back.

My parents have always been connected to Korean content since they immigrated in 1975. I remember watching 1970s Korean variety shows and dramas. Most of the shows featured Trot and ballad singers. The dramas weren’t anywhere near the production quality of todays K-Dramas or art house cinema.