My Gen Z kids talk to me a lot about performative activism.

The sort of activism that is done online to increase one’s social currency rather than one’s committment to an issue. Individual acts may seem benign. But the aggregate effects can result in misinformation, disinformation, falsehoods, and lies being perpetuated. The spectacles of fake fights and fake issues. Unfortunately, main stream media feeds the beast by constantly referring social media comments.

Social media also gives power to rapid organizing around non-issues with false villains. Asian Americans crowdsourcing to explain Black Lives Matter to their older relatives who don’t speak English. Related commentary included accusing old Asians who don’t speak English about their supposed racism against Black people. Instead of fighting racism where it has power (at their schools or workplace); they fake fought racism where it has no power and accused older Asians, who weren’t even a part of the conversation, of being the real racists.

It gets worse. The disconnect from reality is mind boggling.This seeped into academia. Professor Renee Tajima wanted to do a presentation through Gyopo.us about why older Asians who don’t speak English shouldn’t call the police on Black people. I reached out to someone I know at Gyopo.us. I presented the facts. Older Asian Americans are the least likely to call law enforcement of any group of Americans accross all law enforcement through the entire United States. Why wouldn’t Tajima, a professor and researcher, research data BEFORE coming up with a bad idea and running with it? Because she assumes that her target, older Asians who don’t speak English, can’t join her conversation. Gyopo.us agreed with me and cancelled her presentation.

This is one of the best articles I’ve read about Boba Liberals.

“But their association with liberal ideology and liberalism is simply a means to increase their proximity to whiteness or to pretend to be white themselves,” the Urban Dictionary entry says. “Boba liberals use their Asian background as a platform to speak on behalf of the Asian population in the West, using talking points created by white liberals, which has a tendency to gaslight actual issues faced by the Asian diaspora.”

“Boba liberals occupy the small amount of media coverage that Asians receive,” Liu said. “As someone who self-identifies as a liberal, I only ever see articles by and about Asian Americans who do little to advocate for their community and instead spend more of their time admonishing us for our supposed anti-Blackness or some other aspect they perceive. This is extremely frustrating, as it does nothing to help our community and usually helps [boba liberals] ingratiate themselves to their own liberal establishment niche.”

I call them proxies for white liberal assimilationists.

My nonprofit is the only AAPI focused organization in LA County’s Alternatives to Incarceration Incubation Academy. There are over 100 community based organizations in the cohorts. Mostly Black and Brown (self-described). During a recent in person mixer, I mentioned the above Asian Americans who fixate on old Asians who don’t speak English being anti-Black and calling the police on communities of color.

Everyone in the room was confused by these initiatives or movements (they managed to get a lot of mainstream media coverage). Nobody felt like old Asians who don’t speak English was a problem in their lives or movement building. Nobody thought that Black Lives Matter would really gain traction if old Asians who don’t speak English supported them. Nobody thought that Asians, old or young, calling the police on them was a problem. A few people specifically said, “The Koreans will talk to you. They will hash out things with you. They don’t call the police.” A few people also mentioned that when they do work with Asian Americans the relationships are lasting and meaningful and Asian Americans don’t betray Black people like other groups and even their own.

My daughter got her degree in Political Science and some of my friends are Asian American studies professors. They send me links or gift me books. The Elite Capture of Asian American Politics is a real issue.

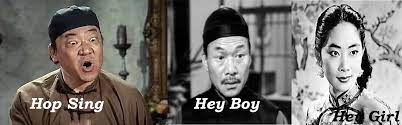

Working-class Asian Americans, Kang acknowledges, have it much worse. They are, in particular, doubly ostracized. To begin with, lacking financial and personal security, they have no basic economic foothold in American society. (It is not a coincidence that the majority of victims of recently publicized anti-Asian hate crimes have been older and low-income.) This socioeconomic alienation is further compounded by the indifference (at best) and condescension (at worst) of Asian American elites, who view them as a reputational risk in the eyes of professional white liberals, both politically and economically.

The implications of this division are serious. As Kang observes, “the millions of Asian working poor have been made entirely invisible, not just by white people but also by their professional brothers and sisters,” many of whose concerns—admission to Harvard, “neuroses about microaggressions,” a “bamboo ceiling” in corporate boardrooms, lack of representation in mainstream media—seem less urgent than matters of affordable housing, safe neighborhoods, good jobs, and quality health care. Kang thus identifies professional Asian Americans like himself as the main obstacle to a meaningful Asian American political identity. While they are busy fighting over access to elite spaces and climbing the ladder of multicultural meritocracy, Kang writes, “the poorest and most vulnerable get stuck with the bill.”

Review of Jay Caspian Kangs “The Loneliest Americans” by Lucy Song is a PhD candidate in Government at Harvard.

I agree with Kang on the above. However, I don’t share his dispair. Kang is clearly removed from his own Korean American community and Asian American activism. Generally, I can tell if an Asian American who writes about identity issues and politics speaks their parent’s language or not. Asian Americans who don’t speak their heritage languages generally have more identity issues. There I said it. He writes on Asian American issues for publications like the New Yorker and New York Times because he’s of Asian heritage and he’s a good writer. It’s not because he actually cares about Asian American issues. More often than not, he seems to be trying to be a great writer by showing off ambivilence masquerading as false sophistication; than he is trying to write with clarity, cogency, or relevance about Asian America.

The professional Asian Americans who act as barriers by performing inclusion.

I’ve been to two seminars organized by the Korean American Law Enforcement Organization at Aroma Spa Center in Koreatown. They invited Korean American nonprofits and “leaders”. Who is this for? It’s performative to give seminars to professional Korean Americans who face no language or economic barriers. At one seminar, a Korean senior man, who needs assistance from law enforcment was shut down when he pleaded for help. My face is still red hot from thinking about this.

I was at a National Immigrant Legal Center’s panel discussion at KIWA. Younger Korean Americans spoke about things that they clearly had not researched. They said that food insecurity is not a problem among Korean Americans because we have great, affordable supermarkets. I almost fell of my chair. There are 40,000 undocumented Koreans in Los Angeles. There’s a huge problem of low wage earning Koreans aging out of the work force and ending up in destitute poverty.

Photos of me organizing and supporting other organizers.

I organize with different people for different issues. There’s overlap. I organize specifically for Korean language access and marginalized Koreans. I do Pan-Asian organizing with older Japanese and Cantonese Americans who have been doing the work since the late 1960s. I organize with BIPOC (Black Indigenous People of Color).

We are willing to show up as an army of one or two or three. We can organize dozens, hundreds, and thousands of people for a protest or a rally.

https://www.instagram.com/reel/CjzEY-bDPwE/ Link to clip where I speak at the Oaxacan led rally to protest racist statements by LA City Council members against Oaxacans, Blacks, and Korean. Nobody was spared their vitriol.